Yep, we’re going there.

Women’s health in the sport and exercise world is finally, finally, starting to garner specific attention. And boy oh boy, are we excited about it. (Whoops, there may have been a pun there…) For many years, it was near-impossible to provide good recommendations to female athletes and runners because the science was almost exclusively based on studies where men were the participants.

We really wanted to do this one justice. So we teamed up with our friend and Naturopathic Doctor Stefania Tiveron to help us get all the good, hard, research-based facts. Stefania is also the owner of Sick Kitty, a tele-naturopathic clinic focused on complementary healthcare for women with hormonal and pelvic health concerns. Read on for research-approved advice from her on how to modify your training to work with your hormones month-to-month, and not against them. Because when you think you’re feeling kind of crappy and not sure why - it’s not in your head, and there are solutions to better manage these times.

If you learn to live, eat, and exercise in harmony with your hormones, then you can take your training (and your health) to a whole new level.

You may not know this, but evaluation of menstrual cycle patterns is a vital sign, like blood pressure. When blood pressure is too high or too low, that’s a sign of a potential health concern. In a similar way, you can view your menstrual cycle patterns as a sign of your underlying health. Tracking your cycle's signs and symptoms is an empowering way to learn about your body and how it changes throughout your cycle. Most people use period apps to track data about their monthly cycle. Good old fashioned pen and paper will do the trick, but period apps are easy and fun to use. My favourite is Clue.

Estrogen and progesterone levels fluctuate throughout your cycle. It’s called a cycle because you make hormones in a cyclical pattern when you ovulate. For people of reproductive age (that were born female even if they no longer identify as female), normal menstrual cycle physiology should result in a healthy regular cycle.

Whether it's for sport, recreation, health, or aesthetics, any person who engages in regular physical activity must be aware that reproductive health is linked to energy availability - with or without disordered eating. Low energy availability, or energy intake that does not meet energy expenditure and other physiological needs (ie walking, talking, breathing), can disrupt the reproductive cycle. In fact, irregular or absent menses may be the first sign of inadequate nutrition for a woman’s level of physical activity.

Low energy availability occurs below an energy availability of 30 kcal/kg of fat free mass per day (1).

How your cycle can change with exercise

When it comes to exercise, there are certain times in your cycle that you will benefit from more exercise, and other times that you will benefit from more rest. This cycling approach is based on normal menstruation patterns, that is, regular and ovulatory cycles. As an adult, a healthy menstrual cycle is anywhere between 21 to 35 days, with 28 days being the average.

If you are aged 16 or older and have never had a period, then please see your doctor. That is known as primary amenorrhea (absence of periods). It may be a presenting symptom of an underlying disorder that requires treatment. If you used to have them but now they've stopped, then that's called secondary amenorrhea. If you are experiencing irregular cycles, including secondary amenorrhea, please consult a qualified primary care practitioner to rule out or consider other potential diseases and disorders of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, ovaries, thyroid, and/or uterus. Amenorrhea is a symptom, not a diagnosis.

Normal menstrual cycle physiology

Before we discuss the cycling approach, let's review normal menstrual cycle physiology.

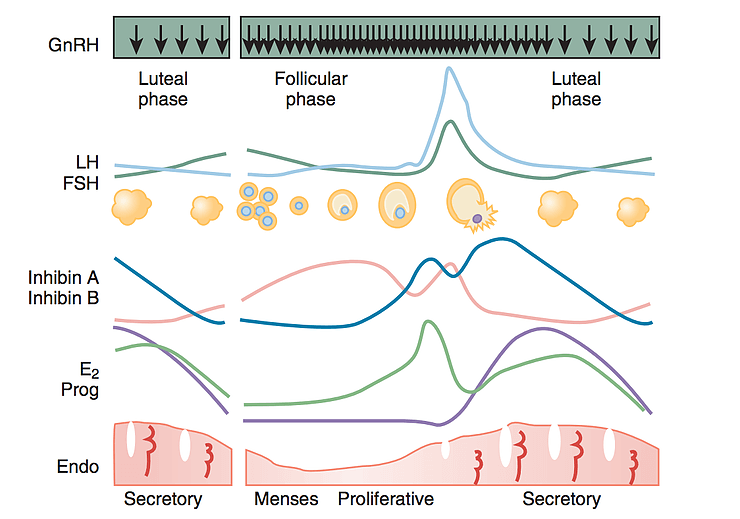

Normal menstruation results from a complex chain of events initiated in the central nervous system. The communication between the brain and ovaries is known as the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis (HPG axis). Two glands are involved, the hypothalamus and the anterior pituitary. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released from the hypothalamus, the part of your brain that acts like a command centre for your hormones. The release of GnRH stimulates the production of follicle-stimulating and luteinizing hormone (FSH and LH) by the anterior pituitary. The ovaries respond by synthesizing the sex hormones, estradiol and progesterone.

Estrogen and progesterone certainly impact menstruation, but the constant and pulsatile release of GnRH is critical to the timing of the menstrual cycle and ovulation. The black arrows indicate the pulse frequency of GnRH in the figure below. Stress disrupts the pulsatile frequency of GnRH, which causes a downstream inhibitory effect on hormones released from the anterior pituitary and the ovaries. The consequence is a mistiming of the release of FSH, LH, a lack of ovulation, and/or a lack of estradiol and progesterone production.

Source: Hall, J.E. 2019. Yen and Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology (Eighth Edition)

Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management; Chapter 7 - Neuroendocrine Control of the Menstrual Cycle, Pages 149-166.e5. Available online 22 February 2018.

Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management; Chapter 7 - Neuroendocrine Control of the Menstrual Cycle, Pages 149-166.e5. Available online 22 February 2018.

The levels of estrogen and progesterone in the blood is what allows the lining of the uterus to thicken and shed every month. Estrogen thickens, while progesterone thins your uterine lining. Progesterone counterbalances the effects of estrogen. If estrogen is yang, progesterone is yin.

How much exercise is “too much?”

What happens when the body is under chronic stress? Stress comes in many forms - over-training, low carbohydrate or caloric intake, low self-esteem, exams, trauma, surgery, a really bad cold - you name it. Your reactions to stress are controlled by a complex set of feedback interactions among the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and the adrenals, known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

Stressors are like messages or incoming signals that your brain receives and interprets in the context of other information from many different brain areas. The brain takes in all of the available information and then decides if stress is needed for protection. Stress is the process of using resources to respond to anything that pushes the system out of balance. This process involves changes to the immune system and endocrine system, which helps mobilize resources to deal with the stressors. In a resilient, healthy and robust person, the HPA axis will return to baseline normal physiology once the stressor has passed.

When the duration or intensity of stress is too high, or you have too many stressors pushing the system at once, then you will likely burn through your resources faster than you can replenish them. This can lead to dysregulation of menstrual cycle physiology.

"…activation of the stress axis, especially activation that is repeating or chronic, has an inhibitory effect upon gonadal hormone secretion. For example, stress and stress hormones inhibit the release of gonadotropin releasing hormone from the hypothalamus, and glucocorticoids inhibit the release of luteinizing hormone from the pituitary and E2 and progesterone secretion by the ovary…" (3).

Chronic stress has a profound effect on reproductive health, especially when the capacity to overcome the stress response has been exhausted. In the context of exercise, this can occur when training is not supported with sufficient rest or recovery, caloric and carbohydrate intake, and hydration; supportive relationships and networks, illness, and certain medical conditions also play a role.

This is what is known as The Female Athlete Triad, described by the American College of Sports Medicine (2007) as the interrelationship between energy availability, menstrual function and bone mineral density. Manifestations of this triad include eating disorders / low energy availability, functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea, and osteoporosis (1).

Let's consider low energy availability as an example. If you're not consuming enough food to meet your own energy needs, then you probably don't have the resources to support a pregnancy. From your body's perspective, health is synonymous with reproduction. Even if you don't want a baby at this particular time, this stressor will trigger a "starvation" response by the hypothalamus to suppress reproduction. Interestingly, this can happen with low carbohydrate diets too, even if you are consuming enough calories. Over time, estrogen levels will drop, which will eventually result in an imbalance in bone remodelling leading to low bone mass or osteoporosis.

If this situation becomes chronic (6 months or longer), it is called hypothalamic amenorrhea (HA). Other causes must be ruled out first before this diagnosis is given. Again, this is your hypothalamus telling you that your energy needs are not being met.

“Exercise is not the cause of menstrual dysfunction. Low energy availability is the issue. Weight variations as low as 2.3 kg can either stop menstruation or trigger its resumption. For most athletes, an increase in dietary energy intake is sufficient to restore menstrual function” (1).

The underlying cause for hypothalamic amenorrhea (HA) is upstream, at the level of the brain. That is where stress is perceived and where stress triggers a cascade of hormonal responses via the HPA axis and its interaction with the HPG axis.

Please be aware that you can't test for HPA or HPG axis dysfunction, per se. At this stage, there is no reliable way to assess it; however, your signs and symptoms are a good place to start, especially menstrual function. I mentioned this earlier but I'll state it again, irregular or absent menses may be the first sign of inadequate nutrition for a person's level of physical activity.

Your menstrual history before taking up training should be evaluated in a detailed health history, one that investigates all potential causes of low energy availability:

- Changes in your training load (ie, sudden or excessive)

- Loss of body fat (less than 17 percent can result in an absence of periods)

- Restrictive diets

- Low carbohydrate intake

- Low protein intake (below 0.7 g/kg)

- Eating disorders

Although low energy availability is the key factor in the triad, there are varied pathways. As you can see, disordered eating is just one of many factors.

If you are unsure if this pertains to you, consider these early warning signs:

- Being involved in a sport that emphasizes body appearance for performance

- Being pressured by influential people like coaches or parents to lose weight as a means to improve performance

- Competitive nature

- Complete involvement in sports, with no other social or recreational activities outside of school

- Training when injured or sick

- Overtraining (outside of scheduled practice times or even when exhausted)

- Traumatic event, injury, poor performance, change in coaching personnel

- Other life stressors (ie family dysfunction, physical or sexual abuse

Cycling Approach

In a 28-day cycle, the menstrual cycle can be broken into these three phases:

- The Menstrual phase (menstruation): days 1–5

- The Proliferative (follicular) phase: days 6–14

- The Secretory (luteal) phase: days 15–28

First day of flow (not spotting) is day one of your cycle, and marks the onset of menstruation. In a 28-day cycle, this phase may occur from days 1-5. This is a time when both estrogen and progesterone levels are low. Low levels signal the pituitary gland to produce Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH). In the ovary, FSH stimulates the development of a follicle containing an egg. This follicle secretes increasing amounts of estrogen - the hormone that dominates the follicular phase.

The follicular phase is a time of increasing amounts of estrogen (relative to progesterone), which makes the body more insulin-sensitive. The metabolism is building up its resources, allowing you to tolerate food better. Translation: yes, you can eat more carbohydrates during this phase, to support your increased training load. But it's not an excuse to eat more junk food.

Estrogen is a growth hormone. Rising levels are associated with thickening and regrowth of the endometrium (the lining of the uterus). It’s primarily responsible for the growth of the breasts and the uterine lining, but it plays a role in growth throughout the female body, including maintenance of bone density. This is because there are receptors for estrogen all over the body. So, estrogen is not just about reproduction, it’s also about healthy growth all over.

Higher estrogen levels also stimulate mood and libido because it boosts serotonin and dopamine. These feel-good neurotransmitters are responsible for making you feeling energized, happy, and motivated.

Taken together, you have the hormonal advantage to eat more and exercise more during the first two weeks of your cycle (5). The metabolism is an adaptive and reactive system that works best in an environment where food intake and exercise output are more closely aligned.

CYCLE YOUR DIET SO YOU ARE EATING MORE AND EXERCISING MORE WHEN ESTROGEN IS HIGH.

Let's go back to the follicle we were discussing in the menstruation phase. If you recall, the follicular phase is a time of increasing amounts of estrogen due to the secretion of estrogen by the follicle. The next phase is the luteal phase, but before it can begin the follicle needs to rupture and release an egg (ovulation). This starts the secretory (luteal) phase. After ovulation, the emptied follicle restructures itself into a progesterone-secreting gland called the corpus luteum.

At this point progesterone dominates (relative to estrogen), making the body a little more insulin-resistant and stress reactive.

Progesterone’s biggest job is to hold and nourish a pregnancy. Considering the potential chance of implantation, your brain is very sensitive to stress at this time. Be cognizant of your need for rest and recovery. Pay attention to how you eat, think, feel, and move. This isn't the best time to push hard. You can still train, but don't exercise to a "burn out" point. You shouldn't feel exhausted for the rest of the day. You want to train in a way that doesn't break you down. Estrogen is anabolic, so it helps you build. Progesterone doesn't have that same effect. It calms the nervous system because it converts to a neurosteroid called allopregnanolone (ALLO) that acts like GABA in the brain. The calming effects of progesterone on the brain pair best with restorative activities.

In this phase of your cycle, you may benefit from a "eat less, exercise less" approach (5). Energy intake and energy expenditure or exercise should always be closely aligned.

CYCLE YOUR DIET SO YOU ARE EATING LESS AND EXERCISING LESS WHEN PROGESTERONE IS HIGH.

To manage the changes in insulin sensitivity, consider eating your biggest meal or highest carbohydrate meal around training. Some people find that limiting their carbohydrate intake after 3pm works best for weight management. Other women find that they sleep better when they eat carbohydrates for dinner. Your body is very adept at cueing you when something is off. Consider your sleep, hunger, energy, mood and cravings. Consider these cues in the context of your needs. For example, if you're hungry, you should eat. But are you hungry because you didn't sleep well, which lowered your mood, which is making you crave a stimulating food like chocolate to boost you up? In this case, you need to consider your sleep hygiene. Maybe you didn't sleep well because your diet has been too restrictive this week. In this case, consider adding more food to better match your energy needs. That could be as simple as eating an extra 5 to 10 bites of a high fibre carbohydrate, like squash or sweet potato to each of your main meals.

Conclusion

Assess your exercise goals, energy requirements and need for rest in the context of your overall stress levels. Many factors push the system out of balance, resulting in a stress response. A little push is good; not all stress is bad. Exercise is a healthy stressor. It forces adaptation and growth, especially when it's supported with rest, recovery, sleep, nutrition, stress regulation, positive mindset, supportive relationships, and healthy forms of challenge.

Your menstrual cycle is a vital sign. Exercise is not the cause of menstrual dysfunction. Low energy availability is the issue. Inadequate nutrition for a person's level of physical activity can lead to a failure in recovery, exhaustion, and dysregulation of the menstrual cycle. An irregular or absent menses may be the first sign of inadequate nutrition for a person's level of physical activity.

Both estrogen and progesterone work together to maintain a regular healthy menstrual cycle. Understanding the effect of these hormones on mood, metabolism, growth, the HPA axis and menstrual function has practical applications for training. Whatever your approach, energy intake and energy expenditure should always be closely aligned.

Dr. Stefania Tiveron is a Naturopathic doctor and owner of Sick Kitty, a tele-naturopathic clinic focused on complementary healthcare for women with hormonal and pelvic health concerns. Improving patient care is my passion. My holistic, patient-centred approach is about empowering and educating my patients because I believe that people need access to information to make informed choices and to improve the quality of their lives. You can find out more about her at:

Email: info@drstefania.com

Website: https://www.drstefania.com/

Insta: https://www.instagram.com/dr.stefania/

From all of us at TRP, thank you for your valuable contribution to our website!

Are you interested in collaborating with us? Drop us a line at info@therunningphysio.ca.

References:

- Sutherland, K. 2014. The Natural Sports Nutrition Masterclass. Special Groups. Session 8. Available: https://www.healthmasterslive.com/lesson/lesson-8-sports-nutrition-masterclass/

- Hudson, T. 2008. Women's Encyclopedia of Natural Medicine. United States of America. McGraw-Hill Education; 2 edition. 528 pages

- Toufexis, D., Rivarola, M. A., Lara, H., & Viau, V. (2014). Stress and the reproductive axis. Journal of neuroendocrinology, 26(9), 573–586. doi:10.1111/jne.12179.

- Waldrop, J. (2005). Early identification and interventions for female athlete triad. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 19(4), 213–220. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.02.008

- Teta, J. 2017. Metabolic Renewal Roadmap. Metabolic Living. 124 pages.